Published: February 2025

Summary

- Everyone can have a balance of feelings, both good and bad,that may change day to day and be affected by life events. If bad feelings are constant it may make it hard for young people to do normal things like going to school or being with their friends. In this case, a young person might be expriencing a mental health disorder.

- Across England in 2023, 20% of children aged 8 to 16 years had a probable mental health disorder, up from 13% in 2017. And 23% of young people aged 17 to 19 years had a probable mental health disorder, up from 10% in 2017. National survey findings from 2017 found that anxiety was the most common type of mental ill health (5.3% of young people), followed by opositional defiant disorder (3.5%) and depressive disorders (1.2%).

- Research evidence suggests that some groups of children and young people are disproportionately impacted by mental health problems largely driven by a complex interplay of social and environmental determinants of poor mental health.

- The Wakefield District School Health Survey in 2022 survey had found decreasing amounts of happiness among pupils and increasing amounts of loneliness (compared to 2020). The proportion of pupils with high mental wellbeing also fell between 2020 and 2022. The 2024 survey findings suggest this decrease in mental health has reversed, with an increase in happiness, a decrease in loneliness, and an increase in the proportion of pupils with high or maximum levels of mental wellbeing. The improvements haven’t all returned back to 2020 (pre-pandemic) levels, and some pupil cohorts have seen weaker improvement than others, or none at all. The overall picture, however, appears to be an improving one.

- Other published data show that in 2022/23, around one-in-five missed 10% or more of their schooling and just over 1,000 pupils missed half of all their school sessions. The rates of persistent and severe absence had been increasing for a number of years prior to 2020, but during and post-pandemic, the rates have risen markedly.

- There are relatively few admissions to hospital for mental health conditions, but around 220 people per year aged under 18 have attended A&E for help with a mental health issue in recent years and a further 135 people per year have attended A&E because of an overdose.

- In 2022/23, there were 177 admissions to hospital of people aged 10-24 years as a result of self-harm. The rate of admissions is similar to the England average and the trend over time is downward.

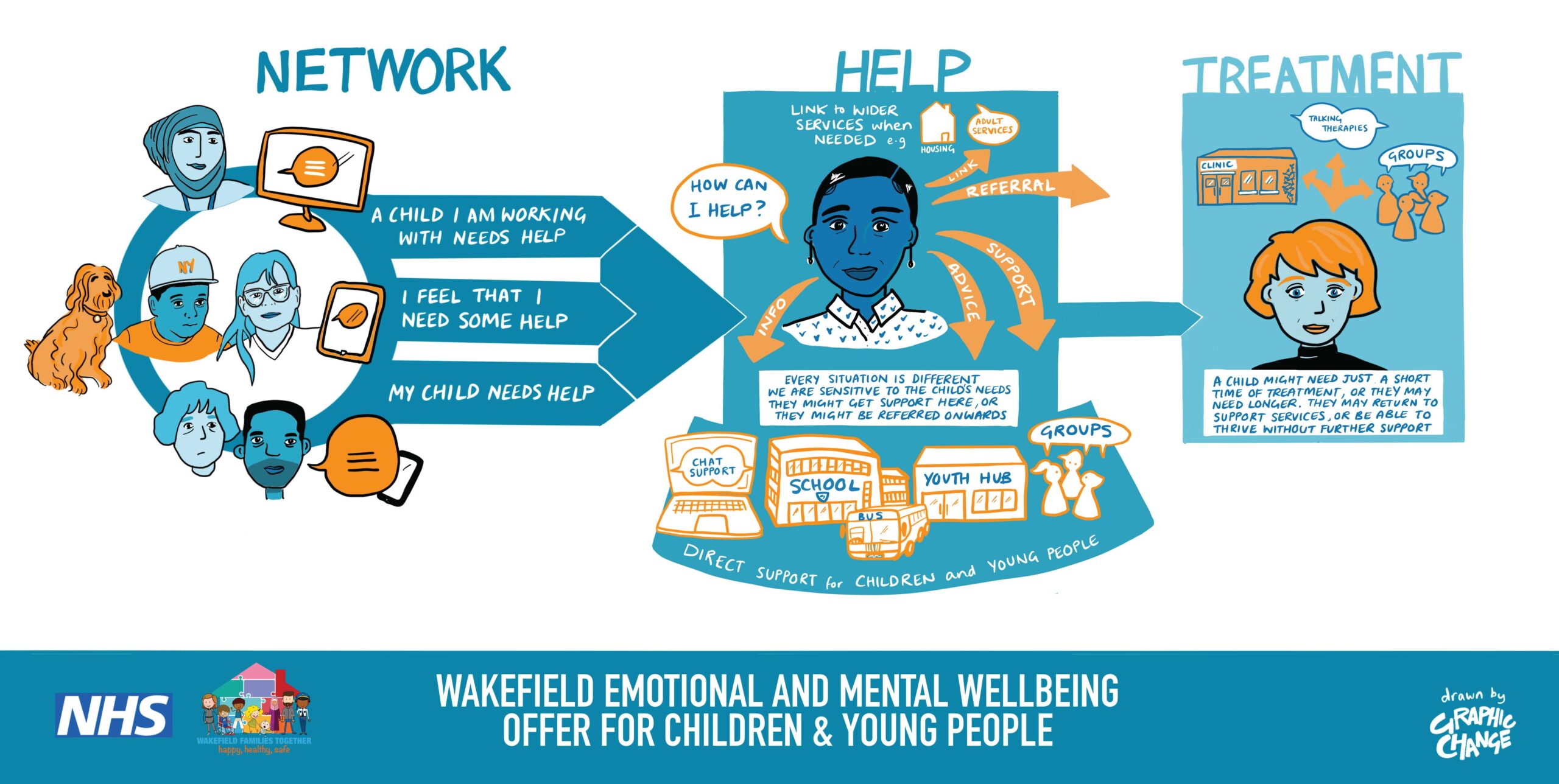

- There is broad emotional and mental wellbeing offer for children and young people living in Wakefield District. Most children are supported within their family and social network. When they need help, they are able to access this easily in different ways. And CAMHS support children who need treatment for their mental health.

- Services for lower-level mental health conditions are delivered by Talking Therapies, Mental Health Support Teams in schools, Future SELPH, Compass, Lumi Nova, and others. These services can provide information, advice, support, referrals and links to wider services, and a variety of engagement methods and settings are offered.

- Self-referrals to CAMHS have doubled since 2020, while the proportion of referrals from GPs has more than halved. In 2023, one in five referrals were given advice and/or signposted to another more appropriate service and a growing proportion of referrals now go on to be assessed by Mental Health Support Teams in schools. There were around 250 emergency referrals to CAMHS in 2023, back down from a peak in 2021 of around 370 referrals.

Introduction

Having good emotional and mental wellbeing usually means that a young person is happy, healthy and safe, but can also include things like having good relationships with other people, a sense of purpose, and a feeling that they are in control of their life. Having good mental wellbeing and health does not mean that young people are always feeling happy and content. Everyone can have a balance of feelings, both good and bad,that may change day to day and be affected by life events.

If bad feelings are constant it may make it hard for young people to do normal things like going to school or being with their friends. In this case, a young person might be expriencing a mental health disorder, which are commonly classified into four major groups [32]:

- Emotional disorders (such as anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, mania and bipolar affective disorder)

- Behavioural disorders (characterised by repetitive and persistent patterns of disruptive and violent behaviour, in which the rights of others, and social norms, are violated)

- Hyperactivity disorders (characterised by inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity)

- Others (such as tic disorders or eating disorders)

Young people can be helped to make their problems feel more manageable. They can also be taught skills and techniques to better prepare them to face challenges in the future. It is possible to get better from mental ill-health.

There are limited data on the prevalence of mental health disorders among children and young people in England, and what data there are usually rely on self-reported indicators of wellbeing or life satisfaction. The 2017 Mental Health of Children and Young People in England [33] survey carried out by the NHS estimated the most common mental disorders among 5 ot 15 year olds were:

- anxiety disorders (5.3%)

- opositional defiant disorder (3.5%)

- depressive disorders (1.2%)

- socialised conduct disorder (0.9%)

Across England in 2023, 20% of children aged 8 to 16 years had a probable mental disorder, up from 13% in 2017. And 23% of young people aged 17 to 19 years had a probable mental disorder, up from 10% in 2017 [1] (Figure 1). If these findings are representative of young people in Wakefield District, then around one-in-five or 10,000 children and young people locally had a probable mental disorder in 2023.

(The NHS England Mental Health of Children and Young People in England survey uses responses to questions from the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) to determine the likelihood (none, possible or probable) of a child or young person having a mental disorder).

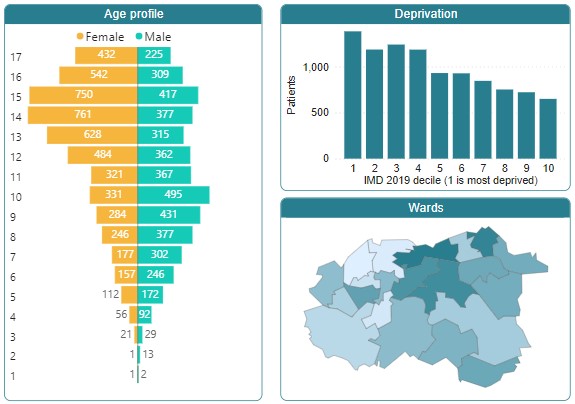

The Local Population

In mid-2023 it is estimated there were 100,000 people aged 0 to 24 living in Wakefield District (79,800 of whom were aged 0 to 18). Generally, there are around 4,000 people per single year of age, but this drops for the late-teen and early-twenties year groups, reflecting migration out of the district to study at university.

It is estimated that between 2023 and 2030 the size of the 0 to 25 population will increase by around 7%. There is uncertainty around this projection, however, and the sub-national population projections won’t be revised until 2025.

At risk groups

Some groups of children and young people are disproportionately impacted by mental health problems due to combinations of social and environmental determinants of poor mental health. These determinants may include,

Ethnicity

Ethnic differences in national surveys are often difficult to interpret because of the small numbers of responses from children in ethnic minority groups. Data from the Wakefield District School Health Survey 2022 does not find differences in mental wellbeing between pupils in the White British ethnic group and pupils in ethnic minority groups, in either Year 7 or Year 9.

One meta-analysis suggests children in the main ethnic minority groups have similar or better mental health than children in the White British ethnic group for common disorders but may have higher rates for some less common conditions, although the causes of these differences are unclear [2]. Analysis of the Millennium Cohort Study suggests ethnic variations in adolescent mental health are partly but not fully accounted for by income, social support, participation, and adversity. After controlling for these, only adolescents in the Black African ethnic group had lower odds of mental health problems [3].

In Wakefield District, the numbers of children and young people in ethnic minority groups have increased over the past decade (Table 1). As a proportion of the 0 to 24 age group, 16.0% of children and young people were in an ethnic minority group in 2021, compared to 9.6% in 2011.

| Ethnic Group | Aged 0 to 24 | |

|---|---|---|

| 2011 Census | 2021 Census | |

| White: English/Welsh/Scottish/Northern Irish/British | 86,336 | 82,099 |

| White: Irish | 52 | 63 |

| White: Gypsy or Irish Traveller | 158 | 102 |

| White: Roma | n/a | 78 |

| White: Other White | 2,345 | 4,380 |

| Mixed/multiple ethnic group: White and Black Caribbean | 635 | 769 |

| Mixed/multiple ethnic group: White and Black African | 265 | 655 |

| Mixed/multiple ethnic group: White and Asian | 627 | 1,174 |

| Mixed/multiple ethnic group: Other Mixed | 327 | 581 |

| Asian/Asian British: Indian | 498 | 674 |

| Asian/Asian British: Pakistani | 2,433 | 3,281 |

| Asian/Asian British: Bangladeshi | 8 | 18 |

| Asian/Asian British: Chinese | 311 | 343 |

| Asian/Asian British: Other Asian | 400 | 705 |

| Black/African/Caribbean/Black British: African | 698 | 1,466 |

| Black/African/Caribbean/Black British: Caribbean | 31 | 44 |

| Black/African/Caribbean/Black British: Other Black | 94 | 441 |

| Other ethnic group: Arab | 155 | 216 |

| Other ethnic group: Any other ethnic group | 174 | 684 |

| All ethnic minorities | 9,211 | 15,674 |

Immigration

Refugees and asylum seekers are more likely to experience poor mental health (including depression, PTSD, and other anxiety disorders) than the general population [4]. A meta-analysis found refugee children experienced high levels of psychological distress in a number of studies looking at PTSD, depression, and high levels of emotional and behavioural problems [5].

Less has been written about the mental health of economic migrants. There’s quite a lot of evidence from the United States for an ‘immigration paradox’ whereby migrant children may fare better than their non-migrant counterparts, despite facing significant socio-economic challenges. There is some UK evidence for this paradox [6], and others have found paradoxical differences between first and second plus generation adolescents on internalizing symptoms (e.g., anxiety and depression) [7].

The 2021 Census shows 5,300 people aged 0 to 24 were born outside the UK, 5.5% of people in this age group. In 2011 the number was 3,800 (4.0%). The 2021 proportion is lower than the regional average (7.9%). Of those age 0 to 24 born outside the UK, the majority (66%) were born elsewhere in Europe, 13% were born in Asia and 12% were born in Africa.

The age breakdown of asylum seekers is not published at local authority level and there is no published data on refugees. There were 23 unaccompanied asylum-seeking children being looked after by the local authority at the end of March 2022. These are children who are in the UK without family and have claimed asylum in their own right.

Sexual orientation and gender identity

People who identify as LGBT+ have higher rates of common mental health problems and lower wellbeing than heterosexual people [8]. A 2018 report by Stonewall found 68% of LGBT people aged 18-24 had experienced depression in the last year and 13% said they had attempted to take their own life in the last year and 52% had thought about it. Almost half of LGBT people aged 18-24 (48%) said they’d deliberately harmed themselves in the last year [9].

Nine percent of females and 4% of males aged 16 to 24 years in Wakefield District say their sexual orientation is lesbian, gay, bisexual or other (2021 Census). One percent, or around 300 people aged 16 to 24 say their gender identity is other than that registered at birth.

Learning disabilities

Research using data from national surveys of child and adolescent mental health found the prevalence of psychiatric disorders was 36% among children with intellectual disability and 8% among children without [13].

Special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) data for 2022/23 show there were 1,720 children and young people in Wakefield District living with a learning disability. 58% of this group are male.

Neurodiversity

Autistic children and young people are more likely than the general population to experience a range of mental health problems [14].

In 2022/23 there a total of 1,663 young people with an EHCP (Education, Health Care Plan) or receiving SEN (Special Educational Needs) support who were living with autism. Of this group, 1,484 had autism recorded as the primary reason for the support, and 179 had autism recorded as a secondary reason. The numbers have doubled since 2015/16 which might reflect improvements in a timely diagnosis and better SEND recording. Among those living with autism in 2022/23, three-quarters were male.

Poverty

Research using the Millennium Cohort Study found that children from low-income families are four times more likely to experience mental health problems by the age of 11 than children from higher-income families [15].

The Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) is calculated for every neighbourhood in England every three or four years. It combines data on issues such as income, employment, education, crime and housing. At the District level, Wakefield is the 54th most deprived district in England (out of 317 districts). The District’s deprivation profile is particularly shaped by high levels of education and skills deprivation and employment and health deprivation are also prominent.

The Department for Work and Pensions make their own annual assessment of the numbers of children living in low-income families and provisional calculations for 2022/23 show 12,795 children aged under 16 living in low-income families (income below 60% of the national median income before housing costs) – 19.1% of all children in this age group [10]. This is slightly lower than the regional ( 23.1%) and UK averages (20.1%). The highest child poverty rates in the region are in Bradford (36.2%) and Hull (28.5%).

At ward level, child poverty is highest in Wakefield East and Wakefield North, and lowest in Wrenthorpe and Outwood West and Stanley and Outwood East (Table 2).

| Ward | children aged under 16 living in low-income families | |

|---|---|---|

| Number | % | |

| Wakefield East | 1,254 | 33.8% |

| Wakefield North | 905 | 26.4% |

| Knottingley | 753 | 25.2% |

| Wakefield South | 708 | 25.2% |

| Hemsworth | 725 | 23.3% |

| South Elmsall and South Kirkby | 909 | 23.0% |

| Airedale and Ferry Fryston | 807 | 22.5% |

| Wakefield West | 816 | 22.3% |

| Featherstone | 672 | 19.5% |

| Normanton | 636 | 19.4% |

| Castleford Central and Glasshoughton | 515 | 18.1% |

| Pontefract South | 518 | 17.9% |

| Pontefract North | 545 | 14.1% |

| Altofts and Whitwood | 521 | 13.6% |

| Ossett | 399 | 13.3% |

| Crofton, Ryhill and Walton | 377 | 13.0% |

| Ackworth, North Elmsall and Upton | 413 | 12.7% |

| Horbury and South Ossett | 331 | 12.3% |

| Wakefield Rural | 324 | 10.9% |

| Wrenthorpe and Outwood West | 339 | 10.3% |

| Stanley and Outwood East | 334 | 10.2% |

Parental mental illness

Parental mental illness can impact significantly on the lives of dependent children through both direct and indirect mechanisms [11]. According to the Children’s Commissioner for England, around a third (32%) of children aged 0-15 live in a household where an adult has moderate or severe symptoms of mental ill-health [12]. Other research finds that around 1 in 3 children lived with at least one parent reporting emotional distress in England in the period 2019 to 2020 [21].

For adults responding to the 2023 Wakefield District Adult Population Health Survey who said they lived with children, 18% (+/- 2.8) of the children enumerated were living with an adult with low mental wellbeing (SWEMWBS score of 7 to 19).

Perinatal mental health (PMH) problems are those which occur during pregnancy or in the first year following the birth of a child. Perinatal mental health problems affect between 10 to 20% of new and expectant mothers [27] and cover a wide range of conditions. Some research suggests prevalence may be as high as 27% [28]. If left untreated, mental health issues can have significant and long-lasting effects on the woman, the child, and the wider family [29].

Midwifery services screen as a matter of course at booking but will also screen at any time if there are concerns when the mother comes to a clinic. Health visitors screen using the Whooley tool antenatally at 28-32 weeks, at postnatal visits at 10-14 days, and at contacts at 6-12 weeks and 9-12 months. Mothers who screen positive to either of the two Whooley questions then complete the PHQ9 tool and if there are concerns may be referred to the specialist perinatal mental health team at the South West Yorkshire Partnership NHS Trust. The GAD-2 and GAD-7 screening tools are also used.

Linking the Maternity Services Data Set (MSDS) with the Mental Health Services Data Set (MHSDS) shows that 11.8% of mothers (416 mothers) who had live births in 2022 had a referral to a specialist perinatal mental health service. 59% of first referrals were during the pregnancy and 41% were after the birth (some mothers were referred multiple times). Mothers with milder presentations may be referred to NHS Talking Therapies or services provided by the third sector.

Adversity and trauma

Children who experience maltreatment, violence, abuse, bullying, loss or bereavement are much more likely to experience mental health problems in later life. An estimated one in three adult mental health conditions is thought to be associated with adverse experiences in childhood [16].

Published data on the factors identified at assessment for children in need [17] in Wakefield District in 2022/23 show that one-third of assessments recorded the domestic abuse of a parent as a factor in the child’s needs, and 30% of assessments recorded parental mental health as a factor. Neglect, alcohol and drug misuse by parents, and emotional abuse were also common factors (Table 3).

| Factor (selected) | Child in need assessments in 2022/23 where factor was identified | |

|---|---|---|

| Number | % of all assessments | |

| Domestic abuse: concerns parent is victim | 1,390 | 34% |

| Mental health: concerns about parent | 1,237 | 30% |

| Neglect | 839 | 21% |

| Alcohol misuse: concerns about parent | 743 | 18% |

| Emotional abuse | 716 | 18% |

| Drug misuse: concerns about parent | 663 | 16% |

| Domestic abuse: concerns child is victim | 442 | 11% |

| Physical abuse: adult on child | 369 | 9% |

| Sexual abuse: adult on child | 245 | 6% |

| Sexual abuse: child on child | 158 | 4% |

| Child sexual exploitation | 156 | 4% |

In 2022/23, Operation Encompass made 2,000 notifications to schools where a pupil had been present at an incident of domestic abuse reported to the police, and a further 1,600 notifications were made for pupils connected with a household where a domestic abuse incident occurred, but the child was not present.

The 2024 Wakefield District School Health Survey [18] found 9% of pupils were often or very often scared to go to school or college because of fear of being bullied. 24% of pupils said they had been bullied because of their size or weight; 10% because of the clothes they wear; and 7% because of a disability or learning difficulty. And among Year 12 students who described their gender as other than male or female, over half (55%) had ever been bullied because of their gender identity, and a similar proportion (49%) of lesbian, gay and bi-sexual students had ever been bullied because of their sexual orientation.

Children and young people in care have poorer outcomes in many areas, including mental and physical health. For example, the rate of mental health disorders in the general population aged 5 to 15 is 10%. For those who are in care it is 45%, and 72% for those in residential care [22]. There is also evidence that anxieties, self-harm, and emotional difficulties are most pronounced in times of transition, e.g., new placements, moving schools, or leaving care [ibid]. On 31st March 2023 there were 635 children in care in Wakefield District. Numbers have tended to increase gradually each year over the past decade. As a rate per 100,000 children, the number in care locally is higher than the national average but lower than the number seen in similar local authorities (our statistical neighbours). In the financial year 2022/23, 8% of children in care had experienced three or more placements during the year. This proportion was lower than the England average (10%) and has improved in recent years.

The 2023 Wakefield District Adult Population Health Survey found 23% of respondents had experienced difficult or distressing events in their childhoods. This increased to 30% among adults living in the top-20% most deprived neighbourhoods. It was also higher among females (27%) than males (18%), and considerably higher among LGBQ+ residents (43%) compared to heterosexual residents (21% ).

Of those respondents with poor mental health, 46% said they had experienced distressing childhood events. The likelihood of having experienced distressing events during childhood was also significantly higher among people who drink at harmful levels (33%), drug users (49%), and tobacco users (38%).

Bereavement

It is difficult to establish the number of local children and adolescents affected by the death of a parent or guardian. Research undertaken nationally suggests that that around 1% of children are likely to experience the death of their mother before they reach the age of 16 years [19]. Applying that figure to the local population would suggest 725 children aged 16 are likely to have experienced the death of their mother, or 45 children per year on average. Based on known mortality trends, the number of children who experience the death of their father by this age could be around twice as high as the estimate for mothers.

Young caring

The Children’s Society estimate that around 9% of young people aged 5-17 care for an adult or family member in England, and that one in three of these will have a mental health issue [20]. The Wakefield District School Health Survey data for 2024 shows 14% of pupils across Years 7, 9 and 12 say they look after or help other people who are disabled or ill for different reasons, including mental health or an alcohol or drug problem. 10% of young carers in the Survey had low mental wellbeing (SWEMWBS score 7-19), compared to 4% of non-carers, a statistically significant difference.

The 2021 Census recorded that unpaid care was provided by 1% of young people aged 5 to 15 years; 4% of young people aged 16 to 20 years; and 6% of young people aged 21 to 24 years.

Contact with the criminal justice system

The prevalence of mental health needs amongst children within the youth justice system has been found to be higher than within the general population of adolescents. Of those children sentenced in England in the year ending March 2020 with a completed AssetPlus assessment, there were concerns in relation to mental health in 72% of cases [23]. Emotional development and mental health can also be an important barrier to stopping a child from offending once they are within the criminal justice system.

In Wakefield District, there were 73 first-time entrants (FTE) to the criminal justice system in the year March 2022. For the calendar year 2022, the local FTE rate per 100,000 population aged 10 to 17 was higher than the England rate but similar to the regional rate.

Liaison and Diversion (L&D) services identify people who have mental health, learning disability, substance misuse or other vulnerabilities when they first come into contact with the criminal justice system as suspects, defendants or offenders. In 2023 there were 300 youth referalls into L&D in Wakefield District, and 38% of those young people were identified with an emotional wellbeing need.

What Local Young People Are Saying About Their Emotional and Mental Wellbeing

The Wakefield District School Health Survey is conducted every two years on a number of different years groups. The 2022 survey had found decreasing amounts of happiness among pupils and increasing amounts of loneliness (compared to 2020) (Figure 2). The proportion of pupils with high mental wellbeing (Shorter Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale*) also fell between 2020 and 2022, although the medium-term trend was less clear. The 2024 survey findings suggest this decrease in mental health has reversed, with an increase in happiness, a decrease in lonliness, and an increase in the proportion of pupils with high or maximum levels of mental wellbeing. The improvements haven’t all returned back to 2020 (pre-pandemic) levels, and some pupil cohorts have seen weaker improvement than others, or none at all. The overall picture, however, appears to be an improving one.

The 2024 survey showed a number of statistically significant inequalities, including

- Female pupils were less likely to feel happy than male pupils (58% vs 68%), more likely to feel lonely (56% vs 41%) and less likely to have high mental wellbeing (21% vs 33%).

- Pupils from an ethnic minority group were more likely to have high mental wellbeing than pupils in the White British ethnic group (30% vs 25%).

- Young carers were less likely to feel happy than pupils without caring responsibilities (51% vs 65%), more likely to feel lonely (60% vs 47%), and less likely to have high mental wellbeing (20% vs 28%).

- Pupils with special needs were less likely to feel happy than pupils without special needs (57% vs 65%), more likely to feel lonely (56% vs 47%) and less likely to have high mental wellbeing (19% vs 28%).

- Pupils from the most deprived neighbourhoods were less likely to feel happy than pupils from the least deprived neighbourhoods (55% vs 63%).

There were significant differences between pupils with low mental wellbeing and others with regard to,

- Fear of going to school because of being bullied – 39% of pupils with low mental wellbeing reported feeling scared often or very often, compared to 6% of other pupils.

- Feeling safe in the area in which they lived – only 51% of pupils with low mental wellbeing said they felt safe in their neighbourhood, compared to 77% of other pupils.

- Feeling safe at school – only 20% of pupils with low mental wellbeing said they felt safe in their neighbourhood, compared to 66% of other pupils.

- Smoking cigarettes – 5% of pupils with low mental wellbeing reported smoking cigarettes at least once a week, compared to 1% of other pupils.

- Vaping – 23% of pupils with low mental wellbeing reported vaping at least once a week, compared to 9% of other pupils.

- Drinking alcohol – 14% of pupils with low mental wellbeing reported drinking alcohol at least once a week, compared to 8% of other pupils.

- Taken cannabis – 28% of pupils with low mental wellbeing reported ever having taken taken cannabis, compared to 17% of other pupils.

- Self-harm – 43% of pupils with low mental wellbeing said they would cut or hurt themselves when worried or stressed, compared to 5% of other pupils.

(* Short Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (SWEMWBS) © NHS Health Scotland, University of Warwick and University of Edinburgh, 2008, all rights reserved.)